Some people will tell you that world-class fame is better than living to a contented old age. Other people disagree. One of those other people might possibly be the protagonist of this tale by Harry Turtledove, master of the counterfactual.

This short story was acquired and edited for Tor.com by senior editor Patrick Nielsen Hayden.

A sunbeam slipped between the slats of the venetian blinds. Anne Berkowitz opened one eye. The clock on the nightstand by the bed had digits big and bright enough to let her read them without her glasses—6:47. She muttered and rolled away from the sneaky sunbeam. She didn’t want to get up so early.

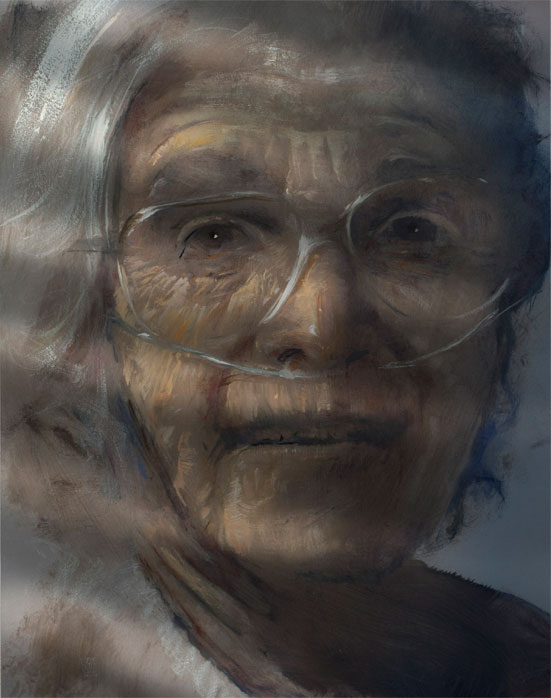

But she was awake. And she was having trouble breathing—not bad trouble, but the kind she had almost every morning after she’d stayed too flat for too long. She reached for the nasal cannula and put it in place. Clear plastic tubing connected it to the green-painted oxygen tank that sat on a wheeled cart by the other side of the bed.

Wrinkled skin hung loose on her arm as she reached out to turn the valve at the top of the tank. She’d never been fat, not once in her eighty-four years. She’d hardly ever been as skinny as she was now, though. If she kept going this way, pretty soon there’d be nothing left of her.

She nodded to herself as oxygen softly hissed through the tubing. Pretty soon there would be nothing left of her. The doctors said she had maybe a year left, maybe two, three at the outside. She worried about it less than she would have dreamt possible even ten years before. As long as it didn’t hurt too much, she was about ready to die.

The oxygen made her feel stronger. The trouble wasn’t her lungs. It was the narrowing of the big artery that came out of her heart. Aortic stenosis, the docs called it, which was the same thing in Greek. An operation—a graft—could fix it, but they said she had not a chance in a thousand of waking up again after they put her under. So here she was, watching her clock wind down.

After a couple of minutes, she reached out and turned the valve on the tank the other way. The oxygen shut off. Anne sat up. Once she got vertical, she was okay, or as okay as she could be these days.

She put on her glasses. The room came into sharper focus. The room . . . Her mouth twisted. The Hebrew Home for the Aging insisted it was an apartment. They could call it whatever they pleased. It still looked like a room to her.

A TV on a stand. A computer on a stand. A bookcase. Novels. History. Poetry. Genealogy. A black-and-white photo of her husband, looking handsome and Mad Men-y in a suit with narrow lapels and a skinny tie. Sheldon had been gone for almost twenty years now, and not a day went by when she didn’t miss him.

Color photos of her son the CPA and of her son the ophthalmologist. Color photos of her grandsons and granddaughters, and a new one of her baby great-granddaughter. Not least among her reasons for keeping the computer was that so many other photos of Elizabeth were on Facebook.

The room—the apartment, if you insisted—also boasted a minifridge and a hot plate. Anne could cook there, after a fashion. She could, but she seldom did. Meals were social times at the Home for the Aging.

She walked into the little bathroom. The tub had a gap in the side so unsteady seniors wouldn’t have to step over it—and so the water couldn’t get more than two inches deep. She’d heard there were some bathrooms with real tubs, but she’d never seen one.

Morning meds first, though. Anne’s mouth quirked. When you got to her age and state of decrepitude, you were what you took. She opened the medicine cabinet. Brown and green plastic pill bottles crowded the shelves, swamping things like toothbrush and deodorant. She took a blood-pressure pill, a stomach-acid suppressor, a vasodilator, a pill to steady her heartbeat, one to hold osteoporosis at bay, and a couple of old-fashioned aspirins for her arthritis, which wasn’t too bad. They all sat on her tongue while she filled a glass with water. Even if it wasn’t long and sticky, it could hold more at once than a chameleon’s.

She brushed her teeth. They were in better shape than the rest of her—most of them were implants. Then she closed the cabinet. As she always did, she marveled at the little old lady who peered back at her from the mirror. How did that happen? How did time get to be so cruel?

Her eyes. She still knew her eyes. Even behind the lenses of her glasses, they were dark and bright and knowing. And her narrow chin hadn’t changed so much, even if she had a turkey wattle under it now. The rest? Wrinkles gullied cheeks and forehead. Her nose was a thrusting beak. Ears as big as Golda Meir’s. Thin, baby-fine hair, white, white, white.

Nothing she could do about any of it, either. Oh, she could dye her hair. She had for a while, when Sheldon was still alive. But she’d been younger then herself. It hadn’t looked so phony as it would now.

After a shower, she started to put on a long-sleeved T-shirt and a pair of heather-gray sweatpants. They were easy, they were comfortable, and what else mattered?

Most of the time, nothing. This morning, Anne caught herself. The kids would be coming today. She’d almost forgotten. She didn’t care about looking nice for anybody here, but for them she did. The T-shirt and sweats went back on the shelf in the closet.

She chose a silk blouse with a floral print and dark blue polyester pants instead. She’d still look like a little old lady, but so what? She was a little old lady. These were the kind of clothes the kids’ grannies put on when they came over to visit.

Her Nikes had Velcro fastenings, not laces. Tying shoelaces wasn’t easy any more. She opened the door, closed it behind her, and walked down the hall to the stairway.

A young Filipino aide smiled at her. “Good morning, Mrs. Berkowitz!” the woman said in accented English.

“Hello, Maria.” Anne’s voice held a vanishing trace of accent, too. If you listened, you could hear it in the vowels and in the slight guttural flavor she gave the r.

She walked down a flight of stairs, holding on to the banister and feeling brave. Going up, she’d take the elevator—that was hard work. But down was okay, as long as you watched where you put your feet.

A garden stretched between her residence block and the dining hall. The same warm, bright, San Fernando Valley sunshine that had woken her poured down on it. A scrub jay in a pale-leaved olive tree screeched at her: “Jeep! Jeep! Jeep!” Anne smiled. The bird figured the garden belonged to it.

She ambled along the smooth concrete path. A hummingbird flashed past her on its mad dash from one flower to the next. Its whole head glowed magenta. Anne admired hummingbirds for their beauty and for their take-no-prisoners attitude. She’d never seen one till she came to America.

Another Filipino attendant wheeled an old man up the path toward her. The man in the wheelchair stared at the orange and yellow flowers as if they were new to him. For all practical purposes, they were. Far gone in Alzheimer’s, he had no idea he’d been here last week, and the week before that, and . . .

“Morning, Ninoy,” Anne said to the attendant as she walked by.

“Morning, ma’am,” he answered. “Nice day, isn’t it?”

“It is, yes.” But Anne frowned once her back was to him and he couldn’t see her do it. The Hebrew Home for the Aging’s Alzheimer’s wing was in a severely modern three-story building near the dining hall. She thanked heaven she’d be dead before she had to go in there. Forgetting whom you’d loved, forgetting who you were, forgetting even how to use the toilet . . . She frowned again, and shook her head. Yes, truly ending was better than a living death like that.

She had oatmeal for breakfast, and canned fruit, and a cup of real coffee, not the decaf she usually drank. Her doctor would cluck when she told him she’d done it. But he was only in his forties, younger than her boys. What did he know? It wasn’t good for her? Nu? So what? She was dying by inches anyhow.

After eating and chatting for a little while with a couple of other residents who still had their marbles, she went over to the visitors’ center. Nothing there had sharp edges or corners. Most of the chairs were at a height convenient for old folks to use without too much bending.

Two big aquariums dominated the main room’s decor. One held freshwater fish; the other, more colorful saltwater. A woman with Alzheimer’s gaped at the saltwater tank. An attendant stood close by, waiting, watching. When the woman’s attention flagged, the attendant gently led her toward the dining hall.

Anne watched the fish herself for a little while. Then she sat down in one of those inviting chairs. No more than half a minute after she had, one of the Hebrew Home for the Aging’s community-outreach workers stuck her head into the visitors’ center and looked around.

“Here I am, Lucy.” Anne waved.

“Oh, good! Glad to see you, Mrs. Berkowitz.” Relief glowed on the outreach worker’s sharp features. She hurried over.

Dryly, Anne said, “I do try to hit my marks.” She knew the Hollywood patter. Movie stars had fascinated her even when she was a girl. And, like so many Angelenos, she’d taken a shot at scriptwriting back in the day. She’d never had one of her own produced, but she’d done uncredited doctoring on a couple that did get made.

“Sure, sure.” Lucy nodded. “And I want to tell you again how wonderful, how impactful, I think it is that you’ve agreed to do this. For today’s middle-school kids to get the chance to talk with a Holocaust survivor and hear what it was like from someone who went through it . . . That’s just marvelous!”

“I was lucky,” Anne Berkowitz said: nothing less than the truth. She tried not to show what she thought of impactful. Like many who’d learned English as a foreign language, she had a strong feel for when it was spoken well and when badly.

“They need to understand what people are capable of doing to other people when, when . . .” Lucy gestured vaguely.

“When everything goes off the rails,” Anne finished for her. She couldn’t blame this middle-aged woman who hadn’t gone through it for not getting why and how the Nazis could have done what they did. She had, and she didn’t get it, either. Which wouldn’t have stopped the Nazis, of course, or even slowed them down.

The community-outreach worker took her phone from her purse to check the time. “They’ll be here at half past eight—it’s a first-period class,” she said, and pointed over to a little meeting room where Anne could talk with the children. “Will you need anything special?”

“If you could get me a water bottle, that would be nice.”

“I’ll take care of it.” Lucy hurried back toward the dining hall.

Anne stood up and walked into the meeting room. She didn’t hurry—she didn’t think she could hurry any more—but she got there. The room held a chair like the one she’d just escaped and a couple of dozen ordinary folding chairs for the kids. Sitting on one of those for longer than a minute or two would have paralyzed Anne’s butt. The eighth-graders probably wouldn’t mind at all.

Lucy came back with the water bottle. She’d brought a big one, which was good. “You’re all ready,” she said.

“Almost,” Anne said. “Could you open it for me, please?” As with tying shoes, her hands weren’t what they had been once upon a time.

“Sure.” Lucy took care of it with ease. She was young enough and healthy enough to do such things without even thinking about them. Anne had been. She wasn’t any more.

A clamor outside said the schoolkids were here. “Keep it down, please!” their teacher said, amusement and despair warring in his voice. Mr. Hauser had taught history at Junipero Middle School since it was a junior high in the 1970s. He still wore his hair long, the way he must have back then, but it was gray now. Despite the hair, he had the unflustered calm of someone who’d dealt with middle-schoolers his whole adult life. He also knew his history. Anne had talked with him on the phone and in person setting this up.

Lucy hustled out of the meeting room to bring in the class. The kids wore uniforms: white or dark blue polo shirts, khakis, dark tartan skirts right to the knee. Mr. Hauser also wore khakis, and an old blue blazer to go with them. He came up and shook Anne’s hand. “Thank you so much for taking the time to talk with us this morning, Mrs. Berkowitz,” he said, pitching his voice both to her and to the students.

“I’m glad to do it. It’s something different,” Anne replied. Most days were pills and oxygen and meals and TV and books. Days doing nothing, days waiting to die. The different days stood out, when there were any.

The students stared at her. They fidgeted on the chairs—not because the chairs were so uncomfortable, Anne judged, but because thirteen- and fourteen-year-olds couldn’t not fidget. There were about twenty of them: white, Hispanic, Asian, one plainly from India or Pakistan, one African American. Junipero was a Catholic school, but Anne would have bet a couple of the white kids were Jewish. A good education was where you found it.

Mr. Hauser turned and spoke to them: “We’ve been studying about World War Two. You remember how, in 1940, Germany invaded Denmark and Norway, and then conquered the Low Countries and France and seemed to be about to win the war. Well, when that happened, Mrs. Berkowitz was living in Amsterdam, the capital of Holland. How old were you then, Mrs. Berkowitz?”

“I was ten—it happened just before my eleventh birthday,” she said. “I wasn’t Mrs. Berkowitz then, of course. I wasn’t Missus anybody. I was only a girl named Anne.”

Some of the kids took notes. Some didn’t, but listened anyway. And some looked as if they wished they were running around in the sweet spring air outside. Well, that was about par for the course.

“You weren’t born in Amsterdam, though, were you?” Mr. Hauser asked.

She shook her head. “No. My father and mother and Margot—my older sister—moved to Holland from Germany in 1933. I stayed with my grandmother in Germany a little longer, and I went to Amsterdam in early 1934.”

“Why did your family move?” the teacher asked.

“Because my father could see how hard Hitler was making things for the Jews. He was a very smart man, my father,” Anne said. “He got a job at a company that made jam, and then at one that turned out spices. Some of my other relatives saw trouble coming, too. Two of my uncles came to America.”

“They got far enough away from the Nazis to be safe, didn’t they?” Mr. Hauser said. “But your family didn’t. What were things like for Jews after the Germans invaded Holland?”

“They were bad, and they kept getting worse and worse. The Germans and the Dutch Nazis made more and more laws and rules against us.”

“There were Dutch Nazis?” a boy exclaimed, his voice right on the edge of being a man’s.

Sadly, Anne nodded. “Yes, there were some. Most of the Dutch people hated Hitler and really hated Seyss-Inquart, the Austrian who ran Holland for him. Without help from people like that, my family never would have made it through the war. But there was a fat fool called Anton Mussert, who led the Dutch Nazi Party and helped the Germans rule Holland. Some people did follow him, either because they truly believed or because they thought that was the side their bread was buttered on.”

“What kind of laws did the Germans make?” Mr. Hauser tried to keep things simple.

“We had to wear yellow stars on our clothes, with Jood on them. That’s Jew in Dutch,” Anne said. “We couldn’t use trams. We had to give up our bicycles. We weren’t allowed to ride in cars. We had to shop late in the afternoon, when there was next to nothing left to buy. We couldn’t even visit Christians in their houses or apartments. We couldn’t go out at all from eight at night to six in the morning. We had to go to only Jewish schools and Jewish barbers and Jewish beauty parlors. We couldn’t use public swimming pools or tennis courts or sports fields or—well, anything.”

“Why did they do that?” a pretty Asian girl asked.

Before Anne could answer, the boy who’d been amazed about Dutch Nazis said, “Is that when they, like, tattooed numbers on the Jews’ arms?”

“Jordan . . .” From the way Mr. Hauser said the name, Anne gathered that Jordan had a habit of breaking in whenever he felt like it.

Not quite smiling, Anne explained, “They only tattooed numbers on you when you went into a camp. If you went in, you probably wouldn’t come out again. We knew that by 1942. Even that early, the BBC said Jews were being gassed. So that summer, when the SS sent my father a call-up notice, he didn’t go. We hid instead, in some rooms above and in back of the place where Father worked.”

“Your family, you mean?” the Asian girl asked. She must have decided she wouldn’t get a sensible answer about why the Nazis tormented the Jews. Anne knew she didn’t have one, not after all these years.

“My family, and a man my father worked with, Hermann van Pels, and his wife and son—Peter was almost sixteen when we went into hiding, about the same age as Margot. And a couple of months later we decided we could fit in one more person. Fritz Pfeffer was a dentist. We were all German Jews who’d gone to Holland and then found out that wasn’t far enough.”

“How big were these rooms?” the Asian girl wondered.

“Not big enough.” The heat with which Anne snapped out the words surprised even her. “Before Dr. Pfeffer moved in, Margot and I slept together in one room. After that, she moved in with Mother and Father, and I got to share that room with the dentist.”

“Eww!” The kids made gross-out noises. Some of them probably had dirty suspicions. They were a lot less naive about the facts of life than she’d been at the same age. Fritz Pfeffer hadn’t been that kind of nuisance, anyway. Plenty of other kinds, yes, God knows, but not that one.

As if plucking the thought from her mind, Mr. Hauser smiled with only one side of his mouth and said, “And you all got along like one big, happy family, right?”

“No!” Anne said, so sharply that everybody laughed—everybody but her. She went on, “By the time the war ended, I never wanted to see any of those people again as long as I lived. My own mother was a cold fish. Auguste van Pels—that was Hermann’s wife—was an airhead. A ditz.”

The students laughed again. Anne didn’t. She hadn’t had those words to describe Mrs. van Pels back then. She couldn’t find any that fit better, though.

And she was just getting started. “Dr. Pfeffer was in love with Dr. Pfeffer. He hoarded food. And he complained I made too much noise and shushed me all the time, even when I just rolled over in bed.”

“Why didn’t you, like, do something to him?” Yes, that was Jordan. Who else would it be?

“I wanted to,” Anne answered honestly. Some of the kids snapped her picture with smartphones. She went on, “I thought about the different things I could do. But I didn’t do any of them. We were stuck there with each other for as long as the war lasted. We couldn’t go anywhere, not unless we wanted to get caught. We had to try to get along.”

“You’ve said some hard things about the people who were in there with you—even about your own mom,” Mr. Hauser said. “What did they think of you?”

“They thought I was stuck-up. They thought I was snippy. They thought I was too smart for my own good,” Anne answered, not without pride.

“Were they right?” a kid asked.

“Of course they were. We were all right about each other. That’s what made getting along so hard,” Anne said.

“What did you do about food?” the pretty Asian girl asked. “Did you have piles and piles of canned things hidden with you, so you wouldn’t need to worry about it?”

She wasn’t just pretty, Anne Berkowitz realized—she was smart, too. She knew which questions to ask. She wasn’t altogether unlike Anne herself at the same age, in other words. “We had some things stored away like that,” the old woman said, “but we tried to save those for emergencies. We had money saved up, too. The people who were helping us used it to get ration books for us, and they used the coupons from them to buy us food. They bought food on the black market, too, for themselves and for us.”

“Can you explain that, please?” Mr. Hauser said.

“You couldn’t get much food with your ration coupons, and you couldn’t get any good food with them,” Anne said. “The Germans stole food from Holland. They stole it from all the places they took over. They wanted it for themselves, and especially for their soldiers. So the Dutch people held on to as much as they could. That was against the Nazis’ rules, and getting that black-market food cost a lot of money. But almost everyone did it. You couldn’t live without it.”

“What if the Nazis caught you doing it?” As usual, Jordan didn’t bother raising his hand. “What did they do to you?”

“They arrested you. Even if you weren’t Jewish, you didn’t want to wind up in a German jail, or in a camp.” Anne paused, remembering. “It would have been right at the start of spring in 1944 when the people we’d been buying things from got arrested. We had to get by on what we could use our ration books for—potatoes and kale.”

“What’s kale?” three kids asked at the same time.

“It’s more like cabbage than anything else,” Anne told them. “This was old, stale kale, and it smelled so bad I had to put a hanky splashed with cologne up to my nose when I ate it. The potatoes were like that, too. We used to try to figure out which ones had measles and which ones had smallpox and which ones had cancer. Those were the kinds of jokes we made.”

“Did things get better after that?” Mr. Hauser asked.

“A little bit, for a while,” Anne said. “But the last winter of the war, the winter of 1944–45, was terrible. Not just for us—for everybody in Holland. They still call that the Hunger Winter. Nobody had anything then. People starved. There was no wood for coffins to bury the dead. People ate tulip bulbs, even. The bread—when there was bread—was gray and disgusting. Everyone knew the Germans had lost. Even they knew. But Holland was off to the side of the way the Americans and English and Canadians were going, so Seyss-Inquart and the Nazis hung on and on.”

“Did you use up all your cans by the time the Hunger Winter was over?” the Asian girl asked.

“Long before then. We were so skinny when Amsterdam finally got liberated. I wondered if we’d live to see it.”

“Was being hungry all the time the worst thing about hiding out for so long?” Mr. Hauser asked.

Anne Berkowitz sent him a hooded look. That was the first dumb question he’d asked. Maybe he didn’t really understand after all. Or maybe he was asking for his students’ benefit. After a moment, she decided to give him the benefit of the doubt. She shook her head. “No. Remember, we were cooped up with each other for almost three years. That was worse. And we never went outside in all that time. That was worse, too. When the Germans in Holland finally quit, we were as white as ghosts. Everyone knew we’d been in hiding till we got some sun. Oh, Lord, fresh air was wonderful!” She smiled, recalling how marvelous it had been.

“Anything else?” the teacher asked. Anne relaxed. The way he put the question showed he knew what he was doing, all right.

She gave it to him: “The worst thing, I think, the very worst thing, was being afraid all the time. So many ways to be afraid. English bombers came over Amsterdam at night. The Americans flew over in the daytime. Most of the time, they’d go on to Germany, but sometimes they’d drop bombs on us. The Germans in Amsterdam would shoot big antiaircraft guns at them, too, and sometimes knock them down. The noise was terrible. It scared all of us—Mrs. van Pels most of all.”

“What would you have done if a bomb hit the building where you were at?” irrepressible Jordan asked.

No doubt at all, though, that that was a dumb question. “We would have died,” Anne said bleakly. Jordan opened his mouth. Then he closed it again—the most sensible thing he could have done.

The Asian girl said, “You were most scared of getting caught, weren’t you?”

“Yes!” Anne’s head bobbed up and down. She’d feared none of the kids would have any idea what she was talking about. Who was she? Just an old lady they’d never met before. But the Asian girl got it, whether the others did or not.

Mr. Hauser saw the same thing. “Good question, Vicki,” he said, so Anne finally had a name for her. “While Mrs. Berkowitz was hiding in Amsterdam, Jean-Paul Sartre—who went through the German occupation in Paris—wrote ‘Hell is other people.’ Maybe he wasn’t talking about this, but maybe he was.”

Some of the kids, Vicki among them, nodded thoughtfully. So did Anne Berkowitz. She’d heard the line before—who hadn’t?—but she’d never applied it to her own predicament till now. She wondered why not. It fit only too well. To hide what she was feeling, she sipped from the water bottle.

“Can you tell us a little about that fear?” Mr. Hauser said.

She sipped again before she answered. “To start with, not everybody who worked at the spice plant knew we were hiding there. And the people who came in to buy things didn’t know, of course. So we had to stay as quiet as we could during business hours. We’d sit on beds and chairs and try not to move unless we had to. We couldn’t flush the toilet. Sometimes we couldn’t even use the toilet—an empty can or a bottle would be a chamber pot. So that was bad. And when we did have to walk around, we never knew whether the noise would give us away.”

“Wow,” one of the eighth-graders said, more to herself than to anyone else.

“That wasn’t all,” Anne said. “We had burglars—more than once. Spices had to do with food, and people got hungrier and hungrier. And I suppose they hoped the office downstairs had money in it, or things they could steal and use to get money or food. The longer the war went on, the more people in Amsterdam stole. It was the only way to get what you needed.”

“Did you hear them breaking in?” Mr. Hauser asked.

“Yes. We ran into them once or twice, too. We would go downstairs at night, when we were the only people there. Sometimes we would put spices into packets. Or we would listen to the BBC on the radio. It was the only way to get news that wasn’t full of German lies.”

“You could get in trouble for that, too, couldn’t you?” the teacher said.

“Oh, yes,” Anne agreed. “For us it was no worry—being a Jew in hiding was a worse crime than listening to the BBC. But people who weren’t Jews did it, too. When the burglars broke in, though . . . They must have been as scared as we were. Almost, anyhow. They weren’t looking for anybody, and we didn’t want to see anybody we didn’t know. We’d shiver for days afterwards.”

“How come?” a girl asked.

Holding her patience, Anne explained, “Because even a burglar could turn us in to the Nazis. He’d probably get a reward if he did. If he knew we were Jews, or if he just guessed . . .” Her voice trailed away. She drank more water.

“Were your rooms hidden well?” Mr. Hauser asked.

“You couldn’t tell they were there just by looking,” Anne answered. “There was a bookcase built in front of the doorway on the second-floor landing. It was attached with hooks. But it wouldn’t keep anybody out who really wanted to come in. That was what we were most afraid of—a fat SS sergeant or a bunch of Dutch Nazis who would have packed us off to Auschwitz.” Her mouth narrowed. “If that had happened, I wouldn’t be sitting here now talking to you.”

“But it didn’t,” Mr. Hauser said. “You all made it through till the Germans surrendered.”

“That’s right.” Anne Berkowitz looked across almost seventy years. “Those were strange times. The Germans in Holland started letting in food a few days before they gave up. They could see it was over. And then, after the surrender, they kept order and handed out the food for a little while, till the Canadians came in.”

“How did they get away with that?” Jordan demanded.

“They were there. They still had guns. They were organized, too, so the Allies used them,” Anne told him. “They even shot a couple of deserters the Canadians handed back to them—this was after the surrender. It kicked up a big stink, and they didn’t get any more deserters back after that.”

She looked across the years again. The Canadians marching into Amsterdam had been so ruddy, so fit, so splendid—so different from the shabby, scrawny, hangdog Dutchmen who’d gone through defeat and five years of occupation. They’d been delicious, was what they’d been. No wonder she lost her cherry that summer, and it wasn’t as if she were the only one: not even close.

Well, that was something the middle-schoolers didn’t need to hear.

She might have lost it to Peter van Pels while they hid together. She’d had a crush on him for a while. Margot had liked him, too, which made things . . . interesting in their cramped, smelly little refuge. But Peter’d stayed almost a perfect gentleman. No, people then hadn’t taken things that had to do with sex for granted. Was that better or worse than the way things worked these days? Anne didn’t know. It wasn’t the same. She knew that.

“What happened to the rest of the Jews in Holland?” Mr. Hauser asked. “How many of them were there?”

“There were about a hundred forty thousand Jews in Holland when the war started—a hundred ten thousand who’d lived there for a long time and the rest refugees like my family,” Anne Berkowitz answered. “Three-quarters of them died. We were lucky—very lucky.”

“I guess you were,” the teacher said. “How did you come to America? Can you talk a little bit about your life after you got here?”

“Sure. Like I told you, two of my uncles were already here. One of them was a citizen after the war. He helped arrange things so I could come. My father and mother moved to Switzerland. My sister stayed in Amsterdam and ended up marrying a Dutchman. We’d all seen too much of each other during the war. After it was over, we broke apart.”

“And you learned English. You learned it just about perfectly,” Mr. Hauser said.

“I was already studying it while we were hiding. I wasn’t very good, but I had a start. I soaked up Dutch like a sponge because I was so little when I went to Holland. I used to tease my parents—it came harder for them. And English came harder for me: I was older by then. I know people can still tell I wasn’t born here.”

“Lots of people who live here weren’t,” Mr. Hauser said. By the way three or four of his students nodded, they weren’t, either.

“True,” Anne said. “Anyway, I came here, and pretty soon I married Mr. Berkowitz. He’d been a gunner in a B-24 during the war. We wondered if I ever heard his plane flying over Amsterdam. I could have—who knows? He ran an advertising business. I helped him out with it here and there. Some of the songs and slogans people heard on radio and TV were mine, but we never said so. You didn’t always admit things like that in those days.”

“It’s different now. Women have more of a chance to be independent,” Mr. Hauser said.

“Oh, yes, and it’s good that they do. But they didn’t back when I was raising a family.” Anne held up a hand. “I’m not complaining. I’ve had a good life. Sheldon and I loved each other a lot as long as he lived. I watched my children grow up and do well, and my grandchildren, and now I’ve got a baby great-granddaughter.”

“Aww,” a couple of girls said.

“And I lived by myself and took care of myself till about a year and a half ago, when I finally got too frail. And now”—Anne shrugged—“I’m here.”

“We’re glad you’re here. We’re glad you’re here all kinds of ways. And we’re so glad you were kind enough to take the time to talk with us this morning,” Mr. Hauser said. “Aren’t we, kids?” The children clapped. A couple of them whooped. It wasn’t the kind of noise the Hebrew Home for the Aging usually heard. Anne Berkowitz liked it anyhow.

Vicki came up to her and held up a phone. “May I take your picture, please?”

“Go ahead,” Anne said. The others had snapped away without asking.

“Sweet.” Vicki took the photo. She turned the phone around and showed it to Anne.

“Looks like me,” Anne admitted.

“I’m gonna put it up on my Facebook page and talk about all the things you told us,” Vicki said. “That was awesome!”

“Facebook . . .” Anne smiled in reminiscence. “We had nothing like that back then, of course. But I used to keep a diary when I was all cooped up. About a year before the end of the war, one of the Dutch Cabinet ministers in London said on the radio that they were going to collect papers like that so they could have a record of what things were like while we were occupied. I went back and polished mine up and wrote more about some things.”

“So you gave it to them?” Vicki’s eyes glowed. “You’re part of history now, and everything? How cool is that?”

A little sheepishly, Anne shook her head. “While the war was still going on, I intended to. But almost the first thing I did after we could come out was, I threw it in the trash.”

“Why?” the Asian girl exclaimed.

“Because I hated those times so much, all I wanted to do was forget them,” Anne Berkowitz replied. “I thought getting rid of the diary would help me do that—and some of the things in there were pretty personal. I didn’t want other people seeing them.”

“Too bad!” Vicki said, and then, after a short pause for thought, “Did throwing it out help you forget?”

“Maybe a little,” Anne said after thought of her own. “Not a lot. Less than I hoped. When you go through something like that, it sticks with you whether you want it to or not.”

“I guess.” Vicki’d never needed to worry about such things. She was lucky, and, luckily, had no idea how lucky she was.

From the doorway to the little meeting room, Mr. Hauser called her name. “Quit bothering Mrs. Berkowitz,” he added. “The bus is waiting to take us back to school.”

“She’s not bothering me at all,” Anne said, but Vicki scooted away.

Lucy walked up to Anne. “I think that went very well,” the outreach worker said. “I’m sure the children learned a lot.”

“I hope so,” Anne said.

“I know I did,” Lucy told her. “So scary!” She gave a theatrical shiver.

To her, though, it was scary like a movie. It wasn’t real. It had been real to Anne, so real she’d wanted to make it go away as soon as she could. As she’d said to Vicki, though, some ghosts weren’t so easy to exorcise.

Lucy wanted to talk some more, but one of the privileges of being old was not listening when you didn’t feel like it. Anne walked out of the meeting room, out of the visitors’ center. She blinked a couple of times as her eyes adjusted to the change from fluorescents to bright California sun.

She started back to her room. She wouldn’t get there very fast—even before she came to the Home for the Aging, one of her grandsons had taken to calling her Flash—but she’d get there.

Or maybe she wouldn’t, not right away. There was a bench by the garden path where the olive tree gave some shade. She sat down on it and looked at the flowers swaying in the soft breeze. A lizard skittered across the concrete and vanished under a shrub.

No, tossing out the diary hadn’t helped that much. She could still remember some of what she’d written in it, better than she could remember most of what happened week before last. She’d wanted to be the best writer in the world. If she’d stuck with Dutch, she still thought she could have done well enough to make some money, anyhow.

In English, it hadn’t quite happened. She’d taken too long to feel at home in the new language. The quiet help she’d given Sheldon, the brushes with Hollywood . . . She shrugged. She’d had more, more of almost everything from adventure to love, than most people ever got.

A hummingbird hovered above the path. After a moment, it decided it couldn’t get any nectar from the flowers on her blouse. It zoomed away. She smiled and watched it disappear.

“The Eighth-Grade History Class Visits the Hebrew Home for the Aging” copyright © 2013 by Harry Turtledove

Art copyright © 2013 by Robert Hunt